I just added this part right here, after most of what is below starting, “Last Saturday…” was written. This turned into more than I envisioned at the start, but I attribute it to artistic inspiration. You could say I got a little bit carried away. Hope you don’t mind my expanded post.

Last Saturday I attended 14th Annual Bear’s Den Fly Fishing Show at their new shop in Taunton, Massachusetts. My friend Peter Frailey, who posted some photos of the Marlborough, Massachusetts, Fly Fishing Show this past January, was also present at The Bear’s Den Show.

When Peter happened my by table Saturday morning, I was tying a peacock herl-bodied wet fly pattern that is listed in Bergman’s book Trout, where I first learned of it, but it can also be found in Mary Orvis Marbury’s 1892 book, Favorite Flies and Their Histories. In fact, before starting to tie the Governor Alvord (I did three of them), I pulled out my traveling copy of Favorite Flies… and referred to the dressing therein. I wanted to put a gold tinsel tag on the fly; Bergman’s recipe does not list a tag. Ah, ha! In Marbury’s book, with no recipes of course, hence my reason to write a new book on the 291 illustrated flies in her book, including both photographs and written recipes; I found upon examination of the color plate, a gold tinsel tag. Before I get too much farther, I better point out that Peter took some photos during the show and posted them on his blog;

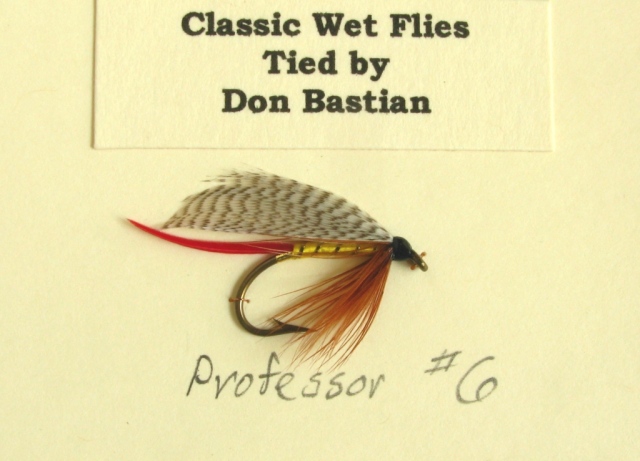

http://www.peterfraileyphoto.com/bearsden2012 but the reason for the title of this post is that he took the photo that appears below.

A curious fact of the Governor Alvord is that it is one of very few peacock herl-bodied wet flies that has a married wing. The Orvis version is on Plate Y of Marbury’s book as a Bass Fly, and its component parts are almost identical to the version in Trout, and having said that, before I present the pattern recipe, I feel compelled to note that this pattern, like many others, is not a “Bergman wet fly.” That phrase is a bit of a misnomer. Bergman’s “wet flies” were simply patterns that were popular in his day, many long before his day, and some of them he tied, sold through his mail-order business, and of course fished with and wrote about in his many articles and four books.

I am probably in part responsible for this situation, because of my association with the reproductions of 499 wet flies that I tied from Ray Bergman’s books that were published in 1999 in the book Forgotten Flies. I wrote the biography on Ray Bergman that appears in Forgotten Flies, and I still consider that work one of my most significant accomplishments. But the publishers selected the title, Ray Bergman and the Wet Fly, for my chapter of that book. Part of the reason the publishers selected that particular title may lie in the fact that Trout had over 600 illustrated fly patterns in it; more than any other book previously published, and a distinction that it held for almost sixty years. I am grateful to have had that opportunity; the timing and fortuitous nature of the project was a concert of cooperation between The Complete Sportsman and myself. I had decided in 1974 when I first tied the Parmacheene Belle that one day I was going to tie all the wet flies from Trout. I was elated when Paul Schmookler approached me in 1997 to inquire of my interest in reproducing the Trout wet flies. You bet I was!

There is though, an undercurrent of belief in the fly tying and fishing industry that clings to the notion that Ray Bergman was responsible for many of the wet flies – 440 in Trout alone – that were published in his book. Trout was a monumental work, as it holds a record of being the only fishing book ever published to remain continuously in print for over fifty years. Trout, in its three editions and multiple printings, has sold over a quarter of a million copies. This is unprecedented for a fishing book.

Some of this is my personal view of course, but in addition to the matter of Ray Bergman being so strongly associated with wet flies, I also feel that the term “MOM flies” slightly and inaccurately misrepresents 19th Century wet fly patterns. Mary Orvis Marbury wrote Favorite Flies and Their Histories, and by the time the book was published, she was head of the Orvis fly tying department, but it is important to note that the Orvis Company was founded in 1856, and it was not until thirty-six years later that Mary penned her epic work. The “MOM fly” or “MOM style flies” references seem to lump all 19th Century wet flies into “her” style, or Orvis style, while in fact there were many other companies creating patterns and selling fishing flies. I prefer the term, 19th Century Wet Flies.

The only wet fly pattern that Ray Bergman originated was the Quebec, which is not listed in Trout but is published in With Fly, Plug, and Bait. The rest of the “Bergman” wet flies were created and published by other individuals and companies, many years prior to Bergman’s writing, with the exception that some of the patterns, such as the creations of Michigan angler Phil Armstrong, Bergman Fontinalis and Fontinalis Fin debuted in Ray’s book. Some flies, like the Professor, pre-date Bergman’s Trout by over one-hundred years. I realize I am getting going on this topic, but am about to wrap it up if you’ll please bear with me.

My reason for discussing this is that many other 20th Century fly tying and fishing authors have been somewhat overshadowed by Bergman’s popularity and his association with wet flies. I merely want to recognize – at the risk of missing a few individuals – because I am not researching any of this information, but rather, writing from my memory – these individuals have also published wet fly patterns, some of their own origin, but most, with recipes identical to or differing from the recipes published in Trout. Bergman’s dressings were most likely representative of the patterns commercially produced in his day.

These individuals and their books have also made significant contributions to the history of wet flies. I also wish to recognize Mike Valla for his recent wet fly book, and his recognition of other fly tiers and authors. Some of these individuals are, in no particular order: George Harvey, Bill Blades, Helen Shaw, Donald DuBois, J. Edson Leonard, Elizabeth Greig, E. C. Gregg, Poul Jorgenson, Ray Ovington, Dave Hughes, Charles F. Orvis, John Alden Knight, Harold J. Noll, Ken Sawada, Sylvester Nemes, and I am sure there are others I have missed. My point is that the origin of some of the hundreds and hundreds of wet fly patterns are known, many others are obscure.

Macro - Don Bastian whip finishing a #6 Governor Alvord wet fly. Photo by Peter Frailey, of Massachusetts, taken Saturday February 25th at The Bear's Den Show. The exposure and lighting makes the red tail and brown hackle appear a little lighter than they are. This version from Marbury's book includes a hackle that is tied palmer from the mid-point of the body. This is a bit of a trick to pull off; actually, pulling it off may not be a trick but instead, a problem, if the feather stem breaks after you have wrapped the body. It is a bit of a trick to tie in the hackle and winding the peacock herl around the feather, but I like the effect. Other 19th Century patterns used this technique.

Governor Alvord – Marbury Dressing:

Tag: Fine oval gold tinsel

Tail: Scarlet quill section. I used a matched pair for a double tail, but most of the 19th century patterns used a single slip of quill.

Body: Peacock herl

Hackle: Brown, tied palmer from middle of body, extra turns in front.

Wing: Slate married to cinnamon or brown

Head: Black

The version of the Governor Alvord in Trout is the same, except minus the tag, and the hackle is either a beard or collar tied in at the head.

I tied three Governor Alvords at the show; the 19th century pattern in a 20th century version. I want to coat the heads with cement to finish them off. Hopefully tomorrow I’ll add the photos to this post.