This post was placed on Wednesday, November 23rd, by “Quill Gordon,” caretaker of The Wantastiquet Lake Trout Club, aka writer of a blog titled, “The View From Fish in a Barrel Pond.”

I know it’s very easy at times, to spend entirely too much time on the internet, but this article, while written primarily as a review of my October visit to The Wantastiquet Trout Club near Weston, Vermont, is focused on my tying of traditional wet flies, it is nevertheless a very entertaining and humorous read, as are some of the other posts on his blog.

http://ghoti62.wordpress.com/2011/11/23/wets/

As a teaser to read Quill’s post, here is a photo of a nice brook trout I landed during my visit:

Brook Trout caught by Don Bastian at the Wantastiquet Trout Club in Vermont

And here is a photo looking north from the dock at our cabin:

The Wantastiquet Trout Club lake near Weston, Vermont. The weather was mostly like this, cloudy, rainy, foggy, misty; but still beautiful, with a captivating allure despite the chill in the air.

My companions for the trip: Derrick, Luke, Paul, and me (left to right), when I was starting to grow a winter beard.

The invitation from one of my Lancaster County friends, Paul Milot, to go on this trip provided a perfect opportunity for me to visit the American Museum of Fly Fishing in Manchester, Vermont, since I had just signed the contract for my book on the 19th Century Orvis fly patterns from Favorite Flies and Their Histories, 1892, by Mary Orvis Marbury. I had previously been in discussion with the folks at the Museum, and it was interesting when speaking with my Pennsylvania friend Paul on the phone, who had called to invite me on this trip. I asked, “Is this place anywhere near Manchester?”

“About 20 miles,” Paul replied.

“Perfect,” I replied, then followed up with this question: “Would it be possible for me to visit the museum during the trip?”

Paul answered affirmatively. As we made our plans, I was delighted to suddenly be presented with a chance to accomplish several things, including a personal visit to the Museum during the trip which afforded me a perfectly-timed opportunity to conduct a little preliminary research for my book. I had previously been planning an imminent trip to Connecticut and Massachusetts anyway, to deliver the remaining seven frames to complete a 10-frame set of mounted wet flies; Plate Nos. 4 through 10 from Trout by Ray Bergman, to a customer who lived near Boston. The patterns in these framed sets are from the Wet Fly Color Plates of Ray Bergman’s Books; 440 out of a total of 483 framed wet flies being sourced from his epic 1938 work, Trout, with the remaining 43 patterns coming from additional flies in Ray Bergman’s other books.

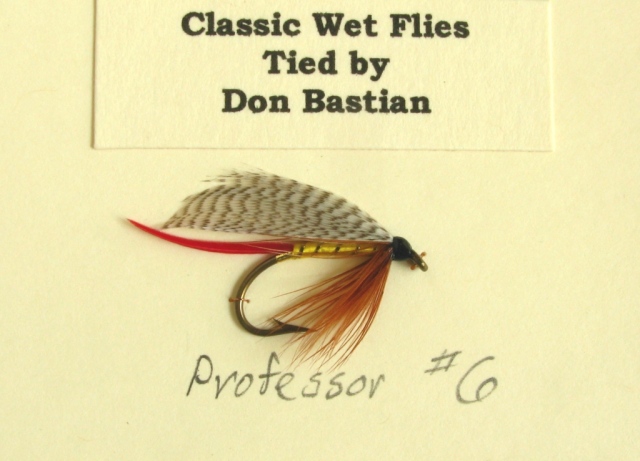

The invitation to join these fellows on this trip was a serendipitous turn of events, plus I got to hang out with friends at the peaceful lakeside camp at The Wantastiquet Trout Club, meet some new friends, tie a few flies, have a little Scotch, relax, and of course – fish! Quill visited our cabin Saturday afternoon to take some photos of the wet fly frames, and he posted some of his pictures of the mounted flies on The View From Fish in a Barrel Pond in his recent post, simply and aptly titled, Wets.

During this, my first-ever visit to Vermont; on Friday afternoon, October 14th, departing the cabin near Weston, Vermont, in the pouring rain so no one wanted to fish, my three companions and I paid a visit to the Museum in Manchester to see Yoshi Akiyama, the Deputy Director. This was the initial stage of research for my upcoming book, and Yoshi graciously spent well over an hour with us and allowed us to see and actually hold – while wearing white cotton gloves – many of the original 32 Plates of mounted flies that were used for Marbury’s book. I had not known these were still in existence until fellow fly tier Paul Rossman informed me. Holding, viewing, and studying these flies was a very moving, spiritual, fascinating experience. Breathtaking. Awe-inspiring. And yes, also enlightening. The flies were individually hand-sewn with white cotton thread onto some type of mat boards which were secured in small wooden frames. It was fascinating to see the homespun cross-hatched thread pattern on the backside of these boards. The sewing process began with the first fly and continued from one pattern to the next, going over the hook bend and silk gut loop or snelled flying-lead of silkworm gut to secure each fly. The flies on each plate were used as models for the hand-painted renderings that were reproduced in Marbury’s book by a 19th Century state-of-the-art process known as chromo-lithography.

An unexpected bonus at the Museum was the display assembled by Mary Orvis Marbury for the 1893 Chicago World Exposition. There are many large display panels, made I think, drawing on my ancient Associate Degree in Forestry Technology and learned experience to recognize some types of wood, of American chestnut. These beautiful glass-covered frames are filled with photographs and mounted flies. This display is essentially a promotional not only for Orvis Company, but is also very clear that Mary Orvis organized it to promote and compliment the geographical theme and layout of her recently published book.

The Orvis display in the Museum captivated me. I returned the next day and spent an hour taking photographs of nearly 150 of the flies in the display, and I skipped over most of the trout flies and hackles. This was a very interesting, fascinating, and enlightening experience. As I later reviewed and zoomed in on various fly patterns, questions I had, as have others, on various components and ingredients – which have been perceived as ambiguous in many cases, and even assumed to be correct for over a century, are in some instances unveiled in a “new light” by these photos. Um, dare I say, different?

This is like detective work and is fascinating to me; part of the process of my book will be to continue and intensify my research and if necessary, make corresponding adjustments in fly pattern recipes. Considering some of the facts I have discovered, I know there are “variations” from some of these accepted Orvis fly recipes. This is confirmed by what I see with my eyes on photographs I took myself. The lack of written pattern recipes in Marbury’s book and the vagaries of visual verification on the painted color plates contributed to persistent questions on some of the materials used. And in fact, this reality hit me during a July 2011 conversation with a fellow fly tier. This realization was the spark of an idea that made me propose a book that would combine the patterns and recipes in a format available to the fly tying public, unlike Forgotten Flies, which, while beautiful, is out-of-print, hard to find, expensive, and at a weight of nearly twelve pounds is too cumbersome, large, and heavy to use as a fly tying desk reference. During that phone conversation, my friend suggested, “Donnie, you should write a book on this.” So the process began.

I would like to give special thanks to my friend Paul Rossman, who is participating as one of the contributing fly tiers for The Favorite Flies of Mary Orvis Marbury. Among a dozen-and-a-half patterns that Paul is graciously providing, there are included some of the same exact flies that he tied, and which were published in the 1999 tome Forgotten Flies. Paul will be accompanying me to the Museum this spring for a weekend session of photographing the original 32 plates with 291 mounted flies. Paul will be using his state-of-the-art computer high-tech camera equipment and his photographic expertise for the addition of photographs of the original 1892 fly plates that will be featured in this book. My original intent was to use the old lithograph images, but when Paul informed me the actual flies are in the possession of the museum, it was like hitting pay dirt. The publication of these photos will provide a treasure trove of information on the flies and will be an invaluable asset to this project.

I shall endeavor to do my best as this project moves forward. Special thanks to Paul and, thank you, to each of my contributing fly tiers! Your work is much appreciated! Your involvement will enhance, embellish, and diversify this project.