A couple months ago I received an e-mail message from a potential customer. He had been searching online for information about fly patterns connected to Albert Nelson Cheney. This is the same A. N. Cheney who co-authored Fishing With the Fly in 1883 with Charles F. Orvis. Cheney is also referred to quite frequently in Mary Orvis Marbury’s 1892 book, Favorite Flies and Their Histories. My customer, Howard Weinberg, reached out to me “because my name kept coming up” during his internet quest for information. It’s good that my name came up in association with historic and classic fishing fly patterns, rather than say, any number of other topics I might be connected to if circumstances were different. During a brief exchange of e-mail messages, Howard and I agreed that I would tie a half-dozen each of the Puffer, a 19th century Adirondack trout fly that was used and probably named by Mr. Cheney, and the Cheney, a Bass Fly pattern that was published in Marbury’s Favorite Flies.

Of the Puffer, Cheney had one in his possession, that he described to “A little brown-eyed maiden, once, looking into my fly book, asked why I had the old, frayed flies tied up in separate papers, and marked, while the nice new flies did not show this care. Had she been of maturer years, I might have quoted Alonzo of Aragon’s commendation of old friends; but, instead, I merely said: ‘The nice new flies I can easily buy, but no one sells such old flies; therefore I take the greater care of them because of their rarity.’ ” Favorite Flies, p. 349.

“On another page we find him looking over these same old flies, and he says; ‘Take for instance this one, with the legend written on its wrapper: Puffer Pond, June, 1867 -thirty-five pounds of trout in two hours. The last of the gentlemen that did the deed.’ This to me, tells the very pleasant story of a week spent in the Adirondacks. I remember, as I hold the ragged, faded fly in my hand, and see that it still retains something of the dark blue of its mohair body and the sheen of its cock-feather wings, that it was one of six flies I had in my fly book that day in June that stands out from other June days, in my memory, like a Titan amongst pygmies. That fly had no name, but the trout liked it for all that, and rose to it with as much avidity as though they had been properly introduced to some real bug, of which this was an excellent counterfeit. That glorious two hours’ time, with its excitement of catching and landing without a net some of the most beautiful and gamy fish that ever moved fin, comes back to me as vividly as though at this moment the four walls of my room were the forest-circled shores of that far-away pond, and I stand in that leaky boat, almost ankle-deep in the water that Frank, the guide, had no time to bail, occupied as he is in watching my casts, and admiring my whip-like rod during the play of the fish or fishes, and in turning the boat’s gunwale to the water’s edge to let my trout in when they are exhausted. It is sharp, quick work, and the blue-bodied fly is always first of all the flies composing the cast to get a rise, until I take off all but the one kind, and then, one after another, I see them torn, mutilated, and destroyed. Later, they will be put away as old warriors gone to rest, and their epitaph written on their wrappings; ‘Thy work was well done; they rest well-earned.’ ” Favorite Flies, pp. 349-50.

“The fly without a name, that awakens memories of ‘that June day that stands out from other June days’ is now called the Puffer.” Favorite Flies, p. 350.

Cheney was instrumental in the creation of the bass fly pattern that bears the heritage of his name. In the 1880’s, Mr. Cheney was visiting the Orvis fly tying room in Manchester, Vermont, seeking to develop a new bass fly pattern. According to the account in Marbury’s book, p. 402: “One summer when Mr. Cheney was staying at Schroon Lake, a few flies, all of them new combinations, were sent to him to try. Among them was a fly like that of the present Cheney fly, but with a black wing. Later in the season Mr. Cheney visited Manchester, when he said, “If that fly had a different wing, it would be just about my idea of a perfect fly for black bass.” Feathers were therefore inspected to find a more suitable wing, and finally those of the mallard with a black bar decided upon. The fly was then made, under Mr. Cheney’s supervision. When finished to his satisfaction he named it the Cheney, and his success with the fly in many different waters has proved the correctness of his theories and conclusions drawn from previous experiments.”

I tied the Puffer fly for Adirondack trout, in sizes #6 and #8, and the Cheney Bass Flies in #2 and #4. Then I went about and prepared to photograph those flies for a blog post in conjunction with the bonus photographs that are included here, before I mailed them to my customer. That’s the day my camera fell from the TV tray and landed on the hardwood floor. This fall rendered the camera a total wreck and useless for anything except a paperweight or perhaps a shooting practice target item from that day forward. Which I felt like doing, but in actuality I think I can still get a trade-in allowance for it in the purchase of a new / used camera. I intended to replace it last month, but Abigail, my Cocker Spaniel, (see the topic “Boat Dog” from June 2013), required urgent surgery for a tumor on her spleen. That set me back almost $1100, so the camera allowance was eaten up by the life-saving operation on the dog. Abigail is doing great, so all is well!

Hence, my original plan to post photos of the Puffer and Cheney flies and photos of an antique Hardy brass-faced reel that was owned by and is engraved with the owner’s name, A. N Cheney, has still come to fruition, though not entirely as originally intended. My deepest thanks go to my customer, Howard Weinberg, for taking these photos of his valuable, collectible Hardy Perfect brass-face reel and the Cheney Bass Flies.

Antique brass-faced Hardy Perfect Reel, once owned by Albert Nelson Cheney, co-author with Charles F. Orvis of their 1883 book, Fishing With the Fly. Photo by Howard Weinberg. Forster Hardy was first granted a full patent for the Perfect reel design in 1889.

A. N. Cheney’s Hardy Perfect Reel, with two #2 Cheney Bass Flies, tied by Don Bastian. Photo by Howard Weinberg. The flies are dressed on vintage Mustad 3906 wet fly hooks.

Hardy Perfect Reel that belonged to A. N. Cheney of Glens Falls, New York; Cheney was the editor of the fishing department of Shooting and Fishing. Photo by Howard Weinberg.

Cheney’s Hardy perfect reel with Cheney Bass Fly tied by Don Bastian. Photo by Howard Weinberg.

I think it is amazing to think that Cheney possibly used this reel to fish his Cheney Bass Fly, or that he fished the Puffer in a wet fly cast for trout. Here is the recipe for the Cheney:

Cheney

Tag: Flat silver tinsel

Tail: Green parrot (or goose shoulder) and barred wood duck

Ribbing: Oval silver tinsel over the rear half of the body

Body: Rear half white floss; front half red chenille

Hackle: Yellow collar

Wing: White-tipped black-barred mallard wing coverts, paired as a spoon wing

Head: Light olive with red band at rear of head

My rendition of the head on this fly was taken from one of my photographs of the actual Plate Fly for the Cheney; it is finished with a light olive thread with a red band, fairly well-done in comparison to most of the flies that sport the rather unkempt look of the reverse-winged head used on most of the patterns back then. I also used Elmer’s Rubber Cement to glue the wing feathers together prior to mounting them to the hook, a technique I borrowed from my assembly of streamer wing hackles – shoulders – cheeks for Carrie Stevens’ fly patterns. This works great for winging some of these large-spoon winged flies that may present problematic feathers or mounting when tied in. The cement is applied just along the stem, for a half an inch or so, then pressed and held together for ten to fifteen seconds. Sometimes I lay the cemented wing down and place an object like an extra pair of scissors on the wing; the weight helps to hold them together while the cement sets.

Below is a photo of the Puffer from the 1893 Orvis Display at the American Museum of Fly Fishing in Manchester, Vermont.

The Puffer wet fly, an Adirondack trout fly pattern. This fly is labeled in Mary Orvis Marbury’s handwriting, from the 1893 Orvis Fly Display, presently held at the American Museum of Fly Fishing in Manchester, Vermont. Photo by Don Bastian.

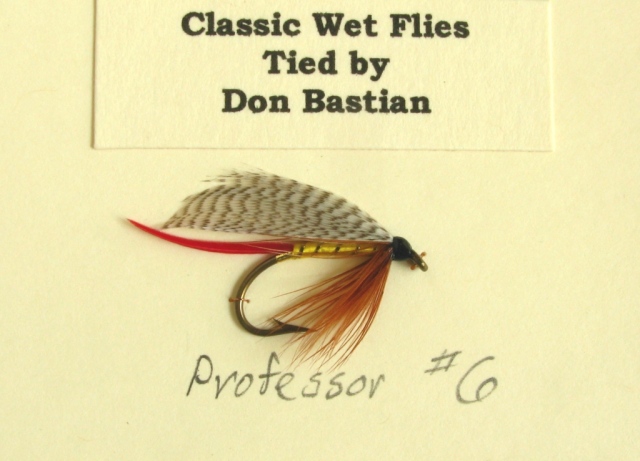

Puffer

Tag: Fine flat gold tinsel

Tail: Red duck or goose quill

Ribbing: Fine flat or oval gold tinsel

Body: Dark blue mohair dubbing

Hackle: English grouse, or dark brown mottled hen

Wing: Iridescent blue rooster or mallard wing sections

Head: Black thread

This dressing for the Puffer is correct according to study of this photo and the information presented in the text of Marbury’s book. I hope you have enjoyed this trip back in time!